< Back

As Asian Americans face racist attacks, a PBS series celebrates their unsung history

May 11, 2020

Like many immigrant children, Daniel Dae Kim didn’t learn of the hard-won American Dream that brought his parents to the United States until later in life. He was a teenager when they finally told him their story, one that resembled those chronicled in PBS’ five-part docuseries “Asian Americans,” a landmark program spanning 150 years that couldn’t arrive at a more timely moment.

They described how, when he was 1 year old, they’d come to the U.S. from South Korea with just $200. Eventually, the family put down roots in Pennsylvania. “From that they built a whole life for themselves and raised three happy, healthy children, one of whom who is fortunate enough to speak to you right now,” said Kim, known for his roles on “Lost” and “Hawaii 5-0.”

Tamlyn Tomita was a junior high student in the San Fernando Valley when she learned that America had incarcerated 120,000 persons of Japanese descent, including U.S.-born Japanese American citizens, during World War II. The “Joy Luck Club” actress would later launch her career with “The Karate Kid Part II” and help tell stories of internment on screen. On that day she went home and asked her father, an LAPD officer: Did this happen to you?

“He said, ‘Yes,’ ” Tomita remembered. “I said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me?’ ”

As long as Asians have been in the United States they’ve helped shape its history but have often been left out of the lessons taught in schools. At home, family histories often go unspoken by older generations who strove through xenophobia, racist legislation, migratory waves, societal shifts, wars and their aftermaths in the pursuit of happiness.

“Asian Americans,” premiering Monday, aims to rewrite that history in vibrant detail. Narrated by Kim and Tomita, it highlights milestones in the history of the country’s fastest-growing demographic — a sprawling group in itself, comprising diverse origin countries, languages and histories — with the help of Asian American scholars, historians and artists like Hari Kondabolu, Viet Thanh Nguyen and Randall Park as well as the descendants of subjects who fought to be seen as more than foreigners in the country they called home.

“We’ve tried to do an Asian American history series for years and years,” said Academy Award-nominated filmmaker and UCLA professor Renee Tajima-Peña (“Who Killed Vincent Chin?”), the producer of “Asian Americans.” Airing during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, the series has taken on even greater urgency amid rising anti-Asian sentiment in America because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Asian Americans are really galvanized and the series is blurring into the conversation of ‘Where do we go next? What does this moment mean?’ ” said Tajima-Peña, who assembled a filmmaking team that included S. Leo Chiang (“A Village Called Versailles”), Geeta Gandbhir (“Why We Hate”) and Grace Lee (“American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs”) to condense an ambitious overview of Asian Americana into five hourlong segments.

“It doesn’t feel like we’re finished with the series,” she said. “It feels like we’re starting this whole new conversation.” In addition to validating the experiences of Asian Americans throughout history, she said, it was important to draw connections between Asian Americans and other communities throughout the series.

That’s why the series finds parallels between the murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese American man who was mistaken for Japanese and beaten to death by white men in Detroit in 1982, and the 1991 killing of 15-year-old African American girl Latasha Harlins by a Korean store owner in Los Angeles, which preceded the Rodney King verdict and exacerbated tensions between the black and Korean communities during the 1992 L.A. Riots.

Tajima-Peña, Oscar-nominated for her 1987 documentary about Chin’s murder, says the recent killing of 25-year-old Georgia man Ahmaud Arbery deserves to be met with the same public outrage by all communities who have been victimized by scapegoating, racism and violence.

“For Asian Americans, the Vincent Chin story is often this touchstone, but you can’t invoke the name and the story of Vincent Chin when there are Ahmaud Arberys happening to black and brown people,” said Tajima-Peña. “For Asian Americans, if we stand up for Vincent Chin, we have to stand up for the Michael Browns, the Eric Garners, and the Ahmaud Arberys. But we don’t always do that.”

“Asian Americans” also feels timely to Kim. In March, actor, producer and director went public with his COVID-19 diagnosis as incidents of anti-Asian violence and harassment were on the rise, targeting Asians as scapegoats for the virus. Being Asian American “has been the source of some of my greatest pride, and greatest pain,” he said in an email. “It means having the benefits of two amazing cultures, and at times, feeling like you’re a true member of neither.

“The story I feel a particular connection to right now is the murder of Vincent Chin,” he said. “I can’t help but see a parallel between his story and the tragic murder of Ahmaud Arbery. To be explicitly clear, I am not equating the African American experience to that of Asian Americans as a general rule. Our histories are very specific and worthy of respect for their own unique reasons, but seeing two young men murdered for no other reason the color of their skin, and then watching the justice system fail them, is a fresh reminder of how far we have to go as a country.””

Moving from the 19th century to the present, “Asian Americans” relates the remarkable stories of notable early Asian migrants. Antero Cabrera, brought from the Philippines to be displayed in a replica Igorot “village” at the 1904 World’s Fair, is remembered by his granddaughter, who notes how he found agency amid the ordeal and started a family in the U.S.

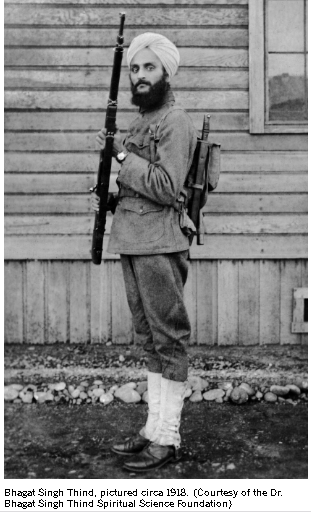

Other figures highlighted include Indian American writer Bhagat Singh Thind, who fought for the United States in World War I and was denied citizenship twice because he was not white; the Chinese laborers who gave their sweat and sometimes lives to building America’s railroads but were largely erased from photographs of its completion; and Moksad Ali, a Bengali Muslim trader who arrived in the 1800s and married an African American woman named Ella Blackman in New Orleans, where his modern-day descendants revisit their multiracial roots on screen.

In subsequent episodes, the series tracks the American-born generations whose lives were upturned by a country that questioned their loyalty; the model minority myth that pitted “good” Asian Americans against other communities of color; the emergence of new alliances and political heroes in the civil rights, farm worker and ethnic studies movements; and the later arrivals of new immigrants and refugees who carved out their own spaces in the changing American landscape.

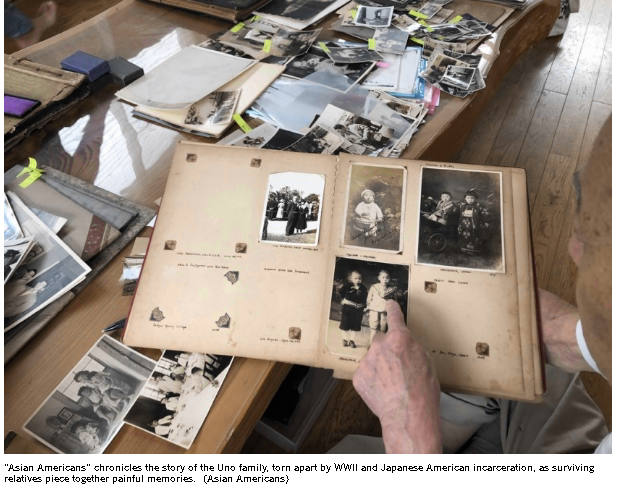

Tomita, of Japanese and Filipina descent, narrates a chapter about the impact of WWII on the Uno family, divided by war and incarceration; Tule Lake-born activist Satsuki Ina, now a prominent voice in the fight to end child detention; and Korean American siblings Philip and Susan Ahn, who fought the Japanese empire by serving in Hollywood and the military, respectively. She thought back to the day she learned of her own father’s story and how that lesson informed her own lasting awareness.

“It was my first awakening to this wrong chapter, the wrong acts committed to our government — how it makes you feel hate and shame,” she said. “That sparked my interest in knowing what happened to my father and to my father’s family and other families of Japanese descent and then other families who now continue to be incarcerated and imprisoned in what they call migrant detention centers.

“The intergenerational trauma that we still witness, I still feel it. I hope I don’t pass it along to my nieces and nephews, but I need to pass along this story so they know it happened and to ensure that it won’t happen again.”

Finding fascinating threads of the Asian American tapestry was easy, said Tajima-Peña. Bringing those stories to life in a visual medium was another story.

“It was really a bear to find archival materials because for the most part Asian Americans were not pictured,” she said. “I’ve seen so many films about, for example, the strikes at San Francisco State and Berkeley. You never see Asians in these films. I used to wonder because I knew people who were there who were a part of the strikes. I thought, ‘Did they cut out the Asians, or did they not even film them?’”

To find footage of Patsy Mink, the Hawaii-born politician who became the first woman of color and the first Asian American woman elected to Congress in 1964, the team sought out footage from the 1960 Democratic National Convention where, according to a contemporary newspaper account, she had given a rousing speech that helped persuade the party to stay the course in the fight for civil rights.

“We knew parts of the convention were televised, so we kept on looking,” Tajima-Peña said. “I said, ‘Find out the day and specifically who was white and speaking around the same time. Look for them, and look through the footage to see if you spot her’ — and that’s how they found her.”

The filmmakers tapped specialty community collections from the Japanese American National Museum and the Museum of Chinese in America in New York, before part of its vast archive was damaged in a fire in January. They also asked people to look in their basements for private troves of home videos, photographs and media that they dusted off, digitized, and preserved as part of the project.

They turned to authors like Vivek Bald, who chronicled the story of Moksad Ali in his book “Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America” and whose work has been vital in establishing the recorded histories of individuals across the spectrum of the Asian American experience. “We knew that Asian Americans are not just East Asian, and we couldn’t do the series without telling those stories,” said Tajima-Peña.

And they invited Asian American figures like Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Nguyen, whose family arrived in the United States in 1975 as refugees from the Vietnam War, to share their own personal histories. The “Sympathizer” author grew up in San Jose, where his parents opened a grocery store and, he remembered, anti-Vietnamese signs posted around their neighborhood sent a stark message to people like him.

“My parents worked 12- to 14-hour days in this store almost every day of the year. My parents were shot in that store on Christmas Eve,” he says in the docuseries, becoming visibly emotional. “I swore one day that I would have an opportunity to rewrite that sign — to write another story.”

Learning about the battles waged and won by predecessors in the Asian American community as well as his own industry, like trailblazing actors Sessue Hayakawa, Anna May Wong and Bruce Lee, is a source of inspiration and encouragement, says Kim.

“Knowing they charted a path where there was none fuels the fire for me to believe in what’s possible,” he said. “The challenges they faced to pave the way for people like me should never be forgotten. After all, you have to know where you started to know how far you’ve come. I’m sure that’s on a fortune cookie somewhere — another Asian American creation, by the way.”

‘Asian Americans’

Where: KOCE

When: 8, 9 and 10 p.m. Tuesday

Rated: TV-14-L (may be unsuitable for children under age 14 with an advisory for coarse language)

Source: https://www.latimes.com/

Comment(s)